brookvale

Last week I went to my first rugby league game. My mate is a big Manly Sea Eagles fan and he got me and my wife into Brookvale Oval with is family to see the Eagles take on the Parramatta Eels. It was a sparklingly perfect winter Sunday afternoon here in Sydney – which, for a New Yorker, felt more like spring.

The Sea Eagles are one of the better and more popular teams in the NRL; between that and the great weekend weather, the place was crowded. I can follow rugby league all right, and enjoyed the game – the Eagles absolutely crushed the Eels, who are apparently having a terrible season. We got to see the Eagles’ star David Williams, known as the Wolfman due to his bushranger-chic look, score three tries (touchdowns) right in front of where we were standing.

But mostly I was just taking in the atmosphere. Brookvale is a venerated place to watch footy – the Sea Eagles have been playing there since 1947, but it dates back almost a hundred years as a sporting facility and showground. It holds 23,000 people (there were 17,000 there that day), so it looks and feels more like a minor league park in American terms. This is partly due to the fact that at least half the teams in the NRL are based in greater Sydney, with teams representing specific areas of the city much the way London football teams do. The Sea Eagles draw fans from Sydney’s Northern Beaches, and probably just about anywhere north of the bridge.

But the small size of the place is why Brookvale has such a great atmosphere. All the seats are general admission, and there’s a big open seating area on a grassy knoll that I’m told is one of the last of its kind in the league. (This was done in American ballparks back in the day too – the old Yankee Stadium had a grassy knoll beyond right field that could seat thousands of extra spectators.) The combination of history, tradition and intimacy results in a vibe that’s much like what Wrigley Field or Fenway Park are for baseball fans – except Brookvale is even more intimate. Wrigley is called “the Friendly Confines” that that tag suits Brookvale too.

It was a great day. The sharp colors (blue sky, green grass, maroon and yellow uniforms), the geometry of the pitch – the white boxes and lines forming a perfect, contained world for this brutal contest – and the ebbing and surging crowd noise lifted my spirits in a way that felt very familiar and comfortable, never mind how foreign the sport is to me. The sun setting over Beacon Hill in the distance and engulfing the pitch, the fans and the gum trees that encircle the grandstand and the grassy knoll in amber light was one of those prolonged moments that makes me fiercely happy to be living in Australia.

Reasons for me to get into the Sea Eagles, should I decide to do so:

- My mate Dave’s opinion counts for a lot in all things

- I feel a strong connection to the Northern beaches

- Lots of history on the team’s side

- You could do worse than maroon and white for colors

- I grew up supporting the Seattle Seahawks, and there’s a nice correlation in the name

- I like birds of prey

- The Wolfman seems like a cool guy

- Spending more winter Sunday afternoons at Brookvale Oval sounds good to me

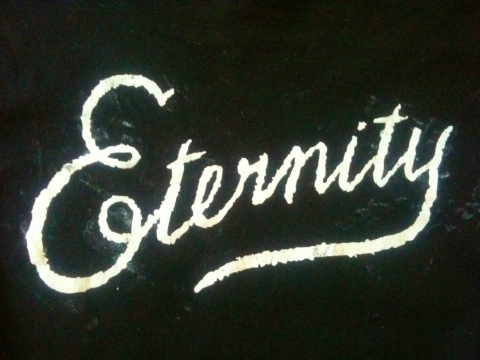

eternity

1. What Happened to My Eternity T-Shirt

After six years, the lettering on my Eternity T-shirt has for some reason started to bleed and smear. It’s a shame, and it’s messy too; but it’s also kind of cool, because it now looks even more like Arthur Stace’s original chalk graffiti.

2. How I First Heard About Eternity

If you’re not from Australia you may not know about Arthur Stace. A true Aussie folk hero, Stace was a reformed alcoholic and born-again Christian who spread the gospel by writing chalk graffiti all over Sydney for decades in the mid-20th century. His one-word message was ETERNITY, written in a beautiful copperplate script despite the fact that Stace was otherwise illiterate. He’s estimated to have written the word 500,000 times over his career. As a longtime friend and graffiti aficionado/perpetrator says, “Dude got up.”

I first read about Stace in Peter Carey’s 30 Days in Sydney, one of a series of travel books written by famous authors. The Booker Prize-winning Carey is probably Australia’s most highly regarded living novelist. I read 30 Days in Sydney in 2005 while still living in New York, shortly after my first trip to Sydney, after I had already started dreaming of migrating here. (As it happens, Carey lives in New York.) Subtitled A Wildly Distorted Account, it’s a feverishly brilliant, sometimes hallucinatory meditation on Carey’s hometown that reads like a work of fiction; it’s one of my favorite books. In many ways I think it’s the best thing he’s written, though it’s probably considered a footnote to his career compared to bestselling novels like Oscar and Lucinda and True History of the Kelley Gang. Reading all of these books was an important part of my preparations for migrating – among other things, they gave me valuable glimpses of the dark side of life here.

In 30 Days, Carey interrupts his drunken, sometimes nightmarish misadventures while on holiday here in Sydney to muse on the enduring local appeal of this legendary figure and his ministry.

I had been at home in New York on the eve of the millennium celebrations and at seven forty-five on that Friday morning, while my wife and sons were still sleeping, I ran quietly down the stairs to witness my other home enter the year 2000… I turned to NBC, where I saw the opera house, the habour bridge. Then Sydney passed into the next century and the bridge suddenly exploded.

Few cities in the turning globe would equal that display at millennium’s end, and yet I, the sentimental expatriate, was less than enchanted and my emotion suddenly cooled. I’d seen this trick before. These fireworks were very similar to that display at our bicentenary in 1988. Then too the bridge grew green and fiery hair. OH WHAT A PARTY the Sydney Morning Herald had written then, and it had been true, the whole town was pissed. We had a classic Sydney rort and we disgraced ourselves with our total forgetfulness of what exactly it was that had occurred in this sandstone basin just two centuries before.

In the heat of our bicentennial celebration, the 50,000 years that had preceded the arrival of the First Fleet somehow slipped our minds. All right, it’s a white-settler culture. It’s what you might have expected, but that does not explain why we forgot the white people too, or most of them. In 1988 we commemorated the soldiers, but the men and women beneath the decks just somehow were overlooked in all the excitement. The twin forces of our history, those two cruel vectors which shape us to this very day, had been forgotten and what we celebrated instead was some imperial and bureaucratic past towards which we felt neither affection nor connection.

Twelve years later I stared balefully at the fiery bridge but as the smoke cleared I spotted an unexpected sign. Just a little to the left of the northern pylon… a three-foot high word was written in illuminated copperplate.

Eternity

Seeing this, all my spleen was completely washed away, and I was smiling, insanely proud and happy at this secret message from my home, happier still because no one in New York, no one but a Sydneysider, could hope to crack this code, now beamed through space like a message from Tralfamador. What fucked-up Irish things it finally meant to me, I will struggle with later, but I cannot even begin to imagine what it might mean to a New Yorker.

An Aussie brandname? Something to do with time? Something, perhaps, to do with those 50,000 years of culture that this city is built on top of? But although 50,000 years is a very long time, it is not an eternity, and it is not why the people of Sydney love this word, or why the artist Martin Sharp has spent a lifetime painting it and repainting it… The secret of Eternity does not belong to Martin but he has been one of its custodians and I was determined to talk to him about it…

The man who designed Cream’s album covers for “Wheels of Fire” and “Disraeli Gears” looked all of sixty when I saw him, hungover, with his handsome face unshaved, and creased with a classic smoker’s skin. But I am of an age myself, and if I noticed the creases, I also noted with envy that his hair, though greying, was thick and strong.

I first saw Eternity when I was a kid, he told me as he rolled his second cigarette. I came out of my house and discovered this chalk calligraphy on the footpath. No one ever wrote anything on the streets in those days. I thought, what’s that? I didn’t think about what it meant. I didn’t analyse it. It was just beautiful and mysterious.

For years and years no one knew who wrote this word, said Martin. It would just spring up overnight. We now know the writer’s name was Arthur Stace. We know he was a very little bloke, just five foot three inches tall, with wispy white hair and he went off to the First World War as a stretcher-bearer. Later he was a ‘cockatoo’, a look-out for his sisters who ran a brothel. Then he became an alcoholic. By the 1930s, when he walked into a church in Pyrmont, he was drinking methylated spirits.

The church had a sign offering rock cakes and tea for the down and out.

Well, Arthur went in for the cakes but he found himself kneeling down and joining in the prayers. That is how he gave up the grog and got ‘saved’ but the God-given task of his life would be granted to him at another church, the Baptist Tabernacle on Burton Street in Darlinghurst.

On the day Arthur came into the Tabernacle the Reverend John Ridley had chosen Isaiah 57:15 as his text. For thus sayeth the high and lofty One who inhabiteth Eternity, whose name is Holy: I dwell in the high and holy place, with him also that is of a contrite and humble spirit, to revive the spirit of the humble, and to revive the heart of the contrite ones.

Eternity, the preacher said. I would like to shout the word Eternity to through the streets of Sydney.

And that was it, said Martin. Arthur’s brain just went BANG. He staggered out of the church in tears. In the street he reached in his pocket and there he found a piece of chalk. Who knows how it got there? He knelt, and wrote Eternity on the footpath.

According to the story, he could hardly write his own name until this moment, but now he found his hand forming this perfect copperplate. That was sign enough. And from then on he would go wherever he felt God call him. He wrote his message as much as fifty times a day; in Martin Place, in Parramatta, all over Sydney people would come out onto their street and there it would be: Eternity. Arthur didn’t like concrete footpaths because the chalk did not show up so well. His favourite place was Kings Cross where the pavements were black.

Actually, God did not always send Arthur to write on the footpaths. Once, for instance, He instructed him to write Eternity inside the bell at the GPO although, Martin Sharp told me, the dark forces may have tried to rub it out since then. Of course he didn’t have permission. Arthur always felt he had permission ‘from a higher force’.

I didn’t have anything directly to do with that word appearing on the bridge, said Martin, but I have kept it alive; I suppose you could say that I have continued Arthur’s work. The paintings you know, but I have also just finished a tapestry of Eternity for the library in Sydney. I’m pleased Arthur’s work is finally in a library. He was our greatest writer. He said it all, in just one word. Of course he would be amazed to find himself in a library. And imagine, Peter, imagine what he would have felt, on that first day in Darlinghurst, to think that this copperplate he was miraculously forming on the footpath would not only be famous in the streets of Sydney but beamed out into space and sent all around the world.

I stayed with Martin talking for a long time, but we said no more about Arthur Stace. So it was not until much later that [sleepless] night… that I attempted to pin down the appeal of his message, not to Martin whose fascination seems both spiritual and hermetic, but to the less mystical more utilitarian people of Sydney.

You might think this is no great puzzle. But it is a puzzle – we generally do not like religion in this town, are hostile to ‘God-botherers’ and ‘wowsers’ and ‘bible-bashers‘. We could not like Arthur because he was ‘saved’, hell no! We like him because he was a cockatoo outside the brothel, because he was drunk, a ratbag, an outcast. He was his own man, a slave to no one on this earth.

Thus, quietly reflecting on what might be the idiosyncratic, very local nature of our feelings for Eternity, I began to follow the vein back to its source until, like someone who dreams the same bad dream each night, 200 years just vanished like sand between my fingers and I was seeing Arthur Stace as one more poor wretch transported to Botany Bay.

3. Why I Think Peter Carey Is Kind of Wrong About That Last Bit

Carey says the appeal of Eternity to Sydneysiders is “a puzzle” because “we generally do not like religion in this town.” Maybe. But which town is he referring to? The one he is familiar with, one populated with artists and writers? Sydney is a big place, made up of all kinds of people. Just recently I heard an elderly lady speak about the founding of the Uniting Church in Australia in 1977. It was a momentous occasion, the uniting of the Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational churches into one entity with a decidedly progressive agenda – the church’s founding statement called for peace, human rights, the eradication of racism, justice for the poor and protection of the environment, streets ahead of its time compared to the Aussie mainstream. This lady proudly spoke of being there at the commemorate service at Town Hall 35 years ago. Perhaps Carey and his artist mates weren’t paying attention, but it was a big deal all the same.

Just to name one more example, Sydney also has a huge community of Polynesians, many of whom are churchgoers. A lot of them are into hip hop, and might therefore appreciate Arthur Stace as a graf legend as well as a man of faith. See what I mean? Which town are you talking about? What if someone said “We generally do not like art in this town.” It would be a pretty rude and dismissive thing to say, and someone who had devoted their life to it might object, but it might also be true. I recently read the autobiography of Robert Hughes, art critic and author of The Fatal Shore, the essential history of Australia’s convict experience; he had some very bitter things to say about his countrymen and their lack of taste. (Like Carey, he too lives in New York.) So it’s all about perspective.

“We could not like Arthur because he was ‘saved’, hell no! We like him because he was a cockatoo outside the brothel, because he was drunk, a ratbag, an outcast.” I get it, you’re suspicous of religion; and it’s true, there was something a little crazy about him. (There’s something a little crazy about all Christians, or there should be. Christians, and graffiti artists.) But I don’t think it’s fair to Stace to give all the credit to only the first half of his story. And anyway, who are you calling a ratbag, mate?

It’s absolutely true he’s an easy figure to love because of his humble, even miserable origins. And Carey’s spot-on in connecting Arthur’s story to the injustices of the convict past. But the crucial thing is that he was, as Stace himself would have put it, born again. If he had just stayed a drunk, none of this would have happened. He was inspired, and driven, by the tremendous feeling he got from being saved, and he did it in the most elegant and unintrusive (and yes, humble) way – while still getting that mystical, beautiful-yet-terrifying word out to everyone in the city for decades. That feeling is tangible when you look at that word; it speaks for itself. Can you imagine the same impact with a different word – a more pedestrian or “utilitiarian” word? UTILITY! Not really. That, I think, is the reason he’s a legend. Carey seems to have made a puzzle out of something self-evident simply because the faith thing jams his radar. Which I understand; I’m not trying to say you have to have faith to ponder eternity – not at all. I’m just addressing one lapse in his emotional logic. If you think I’m biased feel free to ignore me, but I think this case shows that even people who don’t partake can appreciate the power of faith if it’s genuine and comes from a place of love.

Not to nitpick Carey too much – his tripped-out perspective on Australian life and history constantly informs my own since migrating here, and I’m eternally grateful to him for teaching me the secret of Eternity. It’s something I’ve always taken as a sign that I came to the right place.

my map my summer

So, remember when I submitted footage to Map My Summer, the Australia-wide user-generated film project inspired by Life in a Day? Well, it turned out that two bits of my footage of the bats of Gordon were selected by Amy Gebhardt, the director of the project, and are included in the final Map My Summer film, WE WERE HERE.

That film premiered at a packed screening last Saturday night, before the Australian premiere of Life in a Day, as part of Sydney Film Festival. As a contributor I was an honored guest. Amy and executives from Screen Australia and YouTube introduced the film along with SFF director Clare Stewart. Dr George Miller, the distinguished supervisor of the project, was not there (he is too busy working on Happy Feet 2), but he sent a video greeting. I found myself wondering if at any point the dude who directed The Road Warrior looked at my bat footage.

You can watch the finished product embedded here, or on YouTube’s Map My Summer page, for a few more days at least. (I believe they’ll take it down on Saturday after a week’s run.) It’s about 25 minutes long. My footage occurs twice: once near the beginning, and again about two-thirds of the way through.

To tell you the truth, I spent some time being worried that there would be a conflict of interest; I work for Sydney Film Festival- and I just didn’t know what would happen when that came out. So I kept it on the downlow for weeks, while I was waiting for everything to be confirmed. But it turned out that when my colleagues were delighted when they found out about my part in the film, and wondered why I hadn’t boasted about it before.

The whole thing is a bit ironic. Recently I’ve been wanting to get back into film production, and have been planning a couple of different short film projects as a way of challenging myself. I didn’t imagine that footage of bats I shot on my iPhone would end up being the first effort of mine to be screened in public.

But I’m pleased. In general I think community-based filmmaking is one of the directions the industry is going in. I just took a workshop with Joe Lawlor, who has been doing some terrific things with his Civic Life project – collaborating with local communities on financing and producing films in places as diverse as Newcastle, UK and Singapore. User-generated films might be considered the logical extreme of this. At the very least, it’s one positive step towards making sense of the chaos of online video content.

I’m also happy about being included in this project because of being a recent migrant to Australia. I remember seeing a rude comment on one of the posted invitations for Australians to submit footage of what summer means to them: “Better get ready for hundreds of shitty clips of bands playing at the Annandale.” It was funny, but it also highlighted the fact that I haven’t had time to become cynical about anything here yet. I’m still amazed by so many things others take for granted – like seeing flowers blossoming in the winter and parrots hanging out in my front yard. I wanted anything I submitted to reflect that amazement – and it did.

I didn’t have to make many creative decisions – the bats themselves did all the work. Simply pointing the camera at the level of the horizon produces a pretty astonishing image.

Or, maybe all of that is just a roundabout way of saying it really doesn’t have anything to do with filmmaking – it was all pretty random and I’m just lucky. But that works too.

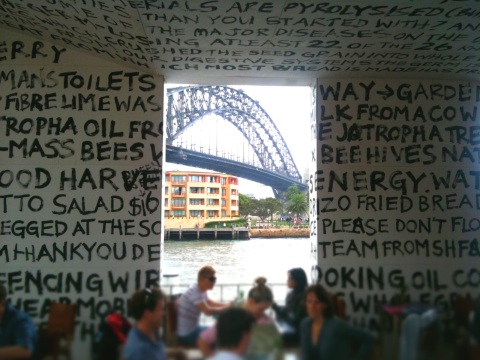

greenhouse by joost

On Saturday, we went to Greenhouse by Joost. It’s a pop-up bar right on Sydney Harbour, at Campbells Cove in The Rocks.

What the heck is a pop-up bar? That’s what I asked my wife when she suggested we go. Apparently it’s a new trend of temporary drinking establishments, the latest hottest thing in our fly-by-night global economy. Constructed with temporary (or reusable) materials, shaped any which way their creators see fit, they spring out of nowhere in hip and convenient locations and stick around for a couple of months or even just a couple of weeks. The owners are thus freed of many of the hassles and overhead of running a business. The point is to make a splash, make some cash, and then fold up and go on to the next thing.

The concept might be familiar to you – temporary venues are now a common sight at arts festivals and in urban parks during the summer. Many of them are sponsored by large corporations. If you’re familiar with the the Beck’s Festival Bar here in Sydney, or the Spiegel Tent in any number of major cities, you get the idea. They can be quite well-appointed, and feel more permanent than they are. My colleagues from the Abu Dhabi Film Festival will probably never forget the impossibly lavish Festival Tent at Emirates Palace.

Greenhouse by Joost is both pop-up business and green art project. It was designed by Joost Bakker, a Dutch-Australian artist, painter, florist and entrepreneur. He built his first Greenhouse in Melbourne in 2006, and since then has done a few of them around Oz. There’s a permanent one in Perth. The one here in Sydney (which is a restaurant as well as a bar) will be up until the end of this month.

The Greenhouse is built entirely of recycled and recyclable materials, it’s carbon neutral, and it’s waste free. But you probably could have guessed all that. The concept of sustainability is becoming a common one. Which is a good thing.

The place feels nice – it’s colorful and inviting; the exterior walls are a vertical strawberry garden. Inside, it’s clean and well-lit. The windows facing the Harbour are huge. As is often the case when green materials are put to good use in building, it’s attractive, with lots of interesting shapes and rough textures in the design. There’s bold visual art and text everywhere you look.

The roof is a great space. The deck is made of unfinished wood. There’s more color, more art, another bar. Most strikingly, there’s a long, long container garden planted with basil and parsley that runs around the whole thing. (The herbs are used in the kitchen. I read that other vegetables are grown there too, but I didn’t see them.) And you simply can’t beat the temporary world-class view. It was unseasonably chilly and wet on Saturday, and we had the roof largely to ourselves. I’m sure it would be hard to find a seat up there in nice weather. We chatted, enjoyed the drizzle, and watched a massive cruise ship depart Circular Quay.

I didn’t eat the food, so I can’t comment on that. I did drink a good amount of ale, and that’s my one complaint: the beers were $10 each. I guess it’s all to support the cause.

Here’s the review in the Sydney Morning Herald.

Notes on the sustainable restrooms: The toilet and sink are designed to work together – to save water I think. When you wash your hands after using the toilet, it flushes. But this backfired when I stepped into the restroom at one point just to wash my hands – I ended up flushing the toilet too, and thus wasting water. Also, the men’s toilet I used did not have a light. I guess this saves a bit of electricity, but using a toilet in the dark is not a practice I’d want to sustain for very long.

adelaide

Last weekend my wife and I visited Adelaide for the Adelaide Film Festival. Amo was on business; I was tagging along. Neither of us had ever been there.

I liked the place much more than I thought I would. I knew little going in: I knew it would feel a lot smaller than Sydney; I had an inkling of a decent arts and music scene; I’d heard about the heat. And a friend said that the huntsmen (large, creepy, dismayingly common spiders) are even bigger and that they jump. Bigger? How much bigger? Like the size of a dinner plate. You gotta be kidding. Even the biggest Amazonian bird spiders are only about the size of a dinner plate. Surely you mean something more like a saucer or a – Wait, did you say they jump? Jump?

It’s a wonder I got on the plane. Anyway, staying in a high-rise hotel, going to movies and wandering around the city center kept me out of the way of any really extravagantly huge spiders, or you would have already heard about it. But there were, oddly enough, lots of crickets and grasshoppers.

Yes, the citizens of Adelaide must have done something to mildly offend the Lord, because there was a harmless but puzzling plague of crickets and grasshoppers going on that weekend – the little buggers had taken over the town, hopping and flying everywhere, swarming around the streetlamps, getting in everyone’s hair – you’d look down and there was one on your shirt or in your beer, bodies piling up in the gutters, in hotel lobbies, in taco stands. The crickets freaked some people out, I think, because they are dark little things with long antennae and tend to look a little more unsavory than they really are. In said taco stand, there was a handwritten sign taped to the counter:

They are crickets. They are NOT cockroaches. They won’t harm you.

Maybe they came for the festival too?

OK, zero expectations, but it wasn’t a few minutes before I was really enjoying Adelaide. For one thing, I liked the layout. It’s very contained, sensible, and attractive, with wide streets forming a perfectly square grid that is, amazingly, completely encircled by a wide swath of green parkland. (Here’s an aerial view.) There are more parks within the grid too. Lots of green. Adelaide is also very pedestrian friendly. There are lots of bike lanes, trams and a number of pedestrianized streets. Rundle Street, one of the main drags in the CBD, becomes for several blocks a long pedestrianized plaza and shopping village, paved with cobblestones and featuring an attractive old arcade, hundreds of shops and sidewalk cafés. Street performers and salesmen with microphones harangue the crowd in every direction. It’s a fantastic place to be on a summer’s evening.

The buildings are attractive, too – a mix of well-preserved 19th century façades and silly but fun hypermodern stuff. For many of these reasons – the parks, the bike lanes, the trams, the old buildings, the street art, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Portland, Oregon. Even the vista out of town reminded me of the west coast – surrounding hills visible down wide, straight avenues. (Of course if it was Oregon, those hills would be a lot bigger. The hills outside of Adelaide are maybe like El Paso’s.)

The Portland analogy only continued the more I walked around and the more cafés, cool shops, record stores and great street art I saw. Clearly the scene punches above its weight. There were two major festivals on last week – the Adelaide Fringe was in full swing too – so of course that colored my outlook. Natives say Adelaide shuts down and gets pretty boring in the offseason. I don’t doubt it. Still, if it’s capable of all of this, it’s got a lot working. On Friday night I did little else but stroll around, enjoying the balmy air, wandering into shops if I felt like it, grabbing a falafel (it was surpsingly good), and sitting and having a couple of beers at a randomly selected pub. I wanted to try the local brew; come to find out the local brew in Adelaide is Coopers – already my favorite Aussie beer and fairly ubiquitous everywhere you go. But I wasn’t complaining.

The other thing about Adelaide is how incredibly friendly the people are. Everyone – cabdrivers, clerks, the terrific box office manager at the Film Festival, who acted like our personal concierge. It was nice, but kind of eerie. Sometimes people would just start having conversations with us, and I think we were taken aback. I hate to feel like such a hardened city type. And I don’t think I’d ever thought of Sydney as being particularly unfriendly. Quite the opposite – I’ve always found Sydneysiders warm and inviting, especially coming from New York. It’s one of the reasons I migrated here. But visiting a smaller place reminded me it’s all about perspective. And it’s true that most Aussies think of Sydney as the big, bad city.

Besides Portland, the other place Adelaide made me think of is, strangely enough, Abu Dhabi, where I’ve spent a lot of time over the past two years. That one is harder to explain – it’s mostly an impression. But it has to do with the wide streets, the uniformly medium-sized buildings, the gleaming postmodern architecture, the perfect grid, all of it bathed in sunshine under perfect blue skies. The comparisons mostly end there – Abu Dhabi’s about as unhip and pedestrian unfriendly as you get. But the impression stayed with me.

So there we are. A weird cross between Portland and Abu Dhabi, in South Australia. Maybe I’ve just been around too much lately – kind of losing a grip on where I am.

This feeling hit me really hard when on Saturday morning we visited the Adelaide Central Market – surely the jewel in Adelaide’s crown, and one of the nicest places I’ve been in Australia. It’s a huge indoor facility that’s exactly like a souk or a bazaar in the Middle East – a bustling maze of stalls filled with produce, meat, seafood, bread and gourmet foods side-by-side with more cafés. We sat at one of these and had coffee and baguettes.

The Central Market was built in the 1860s, and it has a real old-world quality, with lavish architechtural details and decorative tiles, and especially with all of the Italian and Greek purveyors of gourmet cheese, oil, wine and vinegar and sweets. And indeed, I felt nothing so much like I was back in Istanbul (where Amo and I went on vacation last November). Tiles, olive oil, coffee, wait – where am I? Oh, I’m in Australia. It was quite a perceptual slip.

We couldn’t help but think about how Sydney doesn’t have anything like the Central Market, and how much nicer it would be if it did. The thought is a little depressing. But overall, it was a real joy to find a town in my adopted country that is not merely a smaller and less hip and less convenient version of the big city, but is in fact lively and happening and very civilized in its own way. That’s one thing about travel: if you really give a place a chance, you’ll often find that the local flavor overrules all that’s generic and tired about globalization. I definitely look forward to being back in Adelaide.

lindfield rocks

My great downfall is that I can’t blog about just one thing. If you’re one of the seven or eight people who read this page with any regularity, you know this. One week it’s something about surfing. Then I’m going on about current events. Then it’s a review of a falafel joint. I have too many interests.

But if I was the type to focus on only one subject, one thing to blog about, I might make this a page about Lindfield, my neighborhood.

If you don’t know Sydney, trust me on this one: Lindfield is epically suburban and boring. But this is not a dis. Lindfieldites (I don’t know if that’s what they’ve been called previously, but I’m unilaterally declaring it the official demonym starting now) are proud of their boredom. It’s why anyone lives here. It’s safe and green and friendly and really nice – as boring as you wanna be.

But still, I think if someone blogged about this place and did it well, it’d be really interesting. It’d be like a document of suburban life in Australia – a multidisciplinary study involving anthropology, zoology, history, architecture. It could cover the the animals and birdlife native to the area – everything from parrots and wild turkeys to the world’s deadliest spider – the history of the Pacific Highway (one of the oldest roads in Australia – it runs right past our place), the independent bookshop down the street, the behavior of the kids on the train platform, the simmering controversy about high-rise development. It could include more abstract and moody pieces: snapshots of random things that define life here, from the little lizards that constantly scurry underfoot to the twisted piece of wire I saw in the street yesterday that looked like contemporary art.

I’ve already done some of this: I’ve written about our organic garden, and posted video of the local bat colony. But in general I’m not really thinking of imposing such a limit on myself – I’d only get frustrated after a while and be tempted to cover the book about Dubai I just read or my favorite Mexican restaurant in Byron Bay. And I’d get – well, bored. But if I was going to blog about this area in earnest, I’d start with Lindfield Rocks, which has become one of my favorite places to be.

When I call Lindfield “suburban,” I mean by Australian standards. Most Americans who live in metropolitan areas would be impressed by how wild this place is. We’re a ten-minute walk from Garigal National Park, a huge reserve that stretches for miles along Middle Harbour. When you’re inside this reserve – a thickly wooded range of hills and valleys bisected by the Middle River and featuring lots of hiking trails and huge picnic areas – you would never know you were still in greater Sydney, the most populous area of the continent. In most places you can’t see any development or hear traffic at all. You can hike all day, clamber up and down the hills and dells, get lost in the woods, commune with the kookaburras and goannas, blur your eyes and imagine what life was like here before 1788. It truly lives up to its billing as a national park. We’re 10 minutes’ drive in the other direction from the equally sizeable Lane Cove National Park. And there are smaller parks and reserves all over the place. There’s so much nature here I don’t know what to do with it. This is one of the reasons I migrated here.

Lindfield Rocks is at the edge of Garigal, along Two Creeks Track, a hiking trail that runs from our neighborhood to Middle Harbour, some 10 kilometers away. It’s not far from the intersection of two major roads, tucked away down a slope behind a tennis court, hidden in plain sight as it were. I can walk there in 15 minutes – and I often do. Being there always chills me out, makes me feel good about where I’m living.

I first heard of Lindfield Rocks from a friend, a fellow American living here in Sydney who’s an avid rock climber. It’s cherished in the rock climbing community as one of the oldest bouldering sites in Australia. Bouldering basically means climbing rock walls that are relatively low to the ground – so that if you fell you might not die instantly. It’s a kind of freestyle climbing, usually done without a lot of safety gear – as a workout, or just for the sheer pleasure.

I don’t know anything about rock climbing. It’s a pretty involved sport, with its own funky subculture, and lingo as impenetrable as that used by sailors. (Multi-pitching, atomic belay, panic bear, beta flash.) I respect and admire climbers – but I’m not great with heights, so I don’t think I’ll be scaling a cliff at any point. Lindfield Rocks, however, looks pretty manageable to me, and I kind of want to give this bouldering thing a go. I often see climbers at it when I walk down to the rocks, especially on a nice day. They seem to come from all over. It’s probably the only thing in Lindfield that brings outsiders here on a regular basis – the suburb’s greatest distinction, and I wonder how many of the residents know about it. (It’s also just about the only way you’d ever see a beard in this neighborhood.)

I like seeing the climbers when I go there, but I don’t really like to stand around and hawk them while they do their thing, and in general I prefer it when I find that I’m the only one there.

You walk through the woods behind the tennis court, descending the slope on a dirt path, right through a number of big round weathered sandstone rocks, harbingers of what’s down the hill. It’s already much quieter than it is back there on the road, the sound of everything absorbed by the pine needles, the air close. You can hear the sound of the traffic on Eastern Arterial Road, but can’t see it. It sounds strangely pleasant and natural, as if a fast-flowing river lay over there down the hill.

You reach the edge of a shelf, and there’s a staircase cut right into the rock, like something out of Tolkien. It’s the kind of man-made but faintly mysterious detail you find all over these national parks. And at the bottom of the staircase, you realize you’re here – these are the famous rocks suddenly looming right in front of you. A great blunt mass of sandstone, burnished and mottled by millenia of exposure, up to 25 or 30 feet tall in places, stretching away for a hundred yards or more into the woods. There’s a wide flat area at the base where you’re standing; beyond it the hill continues sloping down to the unseen road below.

The thing that strikes you about the rock face is its perfection. It’s perfect for climbing, no doubt – with cracks and rills and folds and other subtle and weird features that only rock climbers have names for running up its surface – but you don’t have to be a specialist to appreciate it. Sydney sandstone comes in many colors and erodes into the craziest forms and shapes – it’s a constant source of wonder no matter where you go in the region – but there’s something in particular about this outcropping. You just want to stare at it. I’m not sure how to explain it. Even with all the flaws it’s so remarkably uniform and vertical for sandstone; as if its changeable nature were suspended for a moment in time, like the parting of the Red Sea. The word wall is right: it really does look like a fortification, a fortress.

Up close, there are a million details. Colors and textures that are different everywhere you look, that seem to change from one day to the next; walking along the wall is like watching a stream constantly change shape and hue as it reflects sunlight. You really understand why rock climbers get so into it – the desire to just be close to and touch this rock, understand the way it flows.

It’s one of those places where nature rises up, reaches out to amaze, makes you stand still and stare, even in a place as prosaic as Lindfield. It seems like it’s… communicating something. I’ve heard the same thing about Uluru. Not that I’m comparing the two.

But though Lindfield Rocks inspires awe, and something a little deeper and harder to quantify, it’s not really a heavy feeling – it’s not ominous, like something’s out to get you, as in Picnic at Hanging Rock. Maybe because the most genteel of suburbs is just around the corner, it feels like a benign place. And it’s so perfectly, so hilariously realized as a thing for people to climb on, or to just look at and enjoy, that it seems like it was done on purpose. Out of friendliness. Despite the sheer weight and dark mass of the thing in front of you, there’s a lightheartedness that bubbles up when you take it in.

It always makes me think of Andy Goldsworthy, the artist who creates surreal and sublime works using only the materials from nature that he can improvise on the spot. His pieces – weird leaf sculptures, capricious rock formations – always look like they might have been left behind by the most primitive humans, or better yet, like they might have just happened by themselves. Many times his pieces are designed to collapse or decay in interesting and beautiful ways – the way a limestone rock does, over vast stretches of time. “Process and decay are implicit.” Part of the point is to make us see the art that’s all around us in nature in the first place – the beauty in all the process and decay. And after a while, it might make you fleetingly wonder why we bother with art at all.

When I visited Istanbul last year I was amazed by a couple of artifacts that were built in remote antiquity, including an Egyptian obelisk brought to Constantinople by the Byzantines that was carved over 3000 years ago. But I wonder if I should be so impressed with bits of granite or marble fashioned by puny men, when Lindfield Rocks has been here for ages and ages longer, and is just as beautiful and – dare I say – artistic. When the Garigal who lent this park its name arrived here 40,000 years ago this wall was already very, very old. Sitting here all this time, waiting for people to come along and make use of it. I wish I could know what the Garigal thought of it. I imagine they liked being here too.

Note: I looked, and could not find a good, comprehensive page about Lindfield Rocks from a rock climber’s perspective, with history, anecdotes, and notes about the various routes (or whateveryacall’em). There are a few pages that are part of larger climbing or travel sites, but all of them are pretty dry and scanty and leave a lot to be desired. Surely there’s gotta be a few rock climbers out there who are also bloggers or web designers? Let’s get to it guys – this place deserves a nice online tribute.

the montgomery method

Recently I posted a piece about Martin Luther King Jr’s global legacy, and later another one about religious unity during the protests in Egypt. Those two strands are tied together in this story on Comics Alliance:

Egyptian Activists Inspired by Forgotten Martin Luther King Comic

(Thanks to my friend Steven, who posted it on Facebook.)

The article details how The Montgomery Story, a comic book about King originally published in 1958 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, was recently translated into Arabic and Farsi by the American Islamic Congress and distributed in the Middle East – including Egypt. The comic is an account of the historic bus boycott led by King in Montgomery, Alabama, and includes a primer on “the Montgomery method” – the program of nonviolent action that King initiated in the American civil rights movement and which proved so crucial in the struggle. The article hints the comic may have had an influence on some Egyptian activists during the resent uprising, and helped shape its largely peaceful nature.

Look, The Montgomery Story probably won’t ever win any artistic awards, but for a comic it is remarkably thorough and insightful in disseminating the spiritual values of nonviolent resistance and… well, love. It even includes a thoughtful recap of Gandhi’s satyagraha movement in India.

The translation and distribution of The Montgomery Story‘s Arabic edition was spearheaded by activist Diala Ziada, director of the AIC’s Egypt office. Ziada tirelessly promotes peace, civil rights and nonviolent change in the region with various media projects and sheer determination. Among her noteworthy projects is the Cairo Human Rights Film Festival, now in its third year.

It’s fascinating to read this Time Magazine profile, published in 2009, identifying Ziada as part of a “soft revolution” of Middle Eastern women pushing for change within Islam. It really highlights how the earthshaking events in Cairo this month have changed the paradigms completely – the story is so right and prescient about some things, and so completely wrong and outdated about others. How quickly our perspective has changed. Note the description of the trouble the first edition of the film festival encountered from the government authorities, and Ziada’s heroic efforts to keep it going:

The censorship board did not approve the films, so Ziada doorstopped its chairman at the elevator and rode up with him to plead her case. When the theater was suspiciously closed at the last minute, she rented a tourist boat on the Nile for opening night – waiting until it was offshore and beyond the arm of the law to start the movie.

I hadn’t heard of this woman until I read this article, and I have to say I’m seriously impressed with her courage and energy and her commitment to nonviolent principles. (And she’s only 28. Ever feel like you’re not doing enough with your life?) In covering the Middle East, the mainstream media has generally focused primarily on victims and bad guys, giving us impressions of violence and pathos and little else. That’s why so many of us were caught off guard with the uprising, a genuine people’s movement defying lines of class, gender and religion, and not dictated by the agendas of elites and foreigners.

The Comics Alliance article admits that since only 2000 translated copies of The Mongomery Story were distributed, its influence on the events in Egypt could not have been widespread. But righteous seeds have a way of germinating at just the right time, and having an impact far greater than it may seem at first. In this letter, Zadia insists the book has had an important effect on those it reaches:

When, at first, we went to print the comic book, a security officer blocked publication. So we called him and demanded a meeting. He agreed, and we read through the comic book over coffee to address his concerns. At the end, he granted permission to print, and then asked: “Could I have a few extra copies for my kids?”

The comic book has been credited with inspiring young activists in Egypt and the larger region… Last week I distributed copies in Tahrir Square. Seeing the scene in the square firsthand is amazing. Despite violent attacks and tanks in the street, young people from all walks of life are coming together, organizing food and medical care, and offering a living model of free civil society in action.

It’s quite an image, a young Muslim woman handing out copies of a 60-year-old comic book about the revolutionary vision of an American Baptist minister, right in the middle of her country’s greatest crisis. As the writer of the Comics Alliance article says, “It’s certainly cool that a comic book starring one of America’s greatest real-life heroes has inspired even one person to take to the streets in the way we’ve seen over the last several weeks.”

Click here for complete PDF versions of The Montgomery Story in Arabic, Farsi and English.

singing bridge pelicans

My friend Jackie got these photos of pelicans feeding at night on the Myall River from the Singing Bridge. Jackie, my wife and I were walking from the beach at Hawks Nest across the bridge to Tea Gardens, where my wife’s parents live in a house right on the river.

The Singing Bridge is so named because it makes a humming sound in the wind. I’ve not heard this phenomenon, but I do like to walk on the bridge as often as possible. It offers terrific views of the Myall estuary, with Port Stephens and Yaccaba head in the distance, and it’s a great place to watch pelicans, black swans, egrets – and with any luck, dolphins, which come up the river to fish in the morning.

As we crossed, I saw the pelicans feeding in the calm, glassy water and tried a few snapshots, but I had a hard time finding a good setting and did not get anything of value. Jackie joined me in shooting almost as an afterthought, did not adjust her camera at all, and the results are really interesting.

I love the way the pelicans are reduced to mere sketches or figures, but very much identifiable as pelicans. No water is discernible; the bird-figures swim in a black field. Perspective is lost completely – the photos almost look like printed patterns – but still the pelicans’ characteristic lazy, contented movements as they feed are apparent, especially in the repetitions between frames.

The plan is to go back to the bridge to recreate this setup, but shoot with video instead, and make a short film with the same aesthetic: pelicans floating on black, nothing else. We’ll see if it can be as serendipitous and oddly perfect as these snapshots.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment